The author of the content describes the experience of setting up an exhibition at Museo Correr in the salons renovated by Carlo Scarpa in the 1950s. They express the overwhelming emotion and honor of being able to display their work in a space where everything must remain exactly as Scarpa intended it, creating a rare case of historicized museology. The Museo Correr is regarded as a sacred place, with the author considering it one of the most religious places in the history of art and architecture. The challenging setting prompts the author to question what they can show to stand alongside masterpieces by artists such as Carpaccio, Giotto, and Bellini.

The author discusses their obsession with tears and how it has been a defining subject of their work since the beginning. They reference a quote from Virgil that translates to “there are tears in (or for) things” and mention their reluctance to delve into the subject of melancholy due to its personal nature. After conducting research, they note that tears have rarely been represented in art history, with classical paintings often portraying pain or sorrow through hidden or averted eyes. The absence of tears in art led the author to incorporate them into their work naturally, viewing them as an emotional pinnacle that has not been explored by male-dominated art culture.

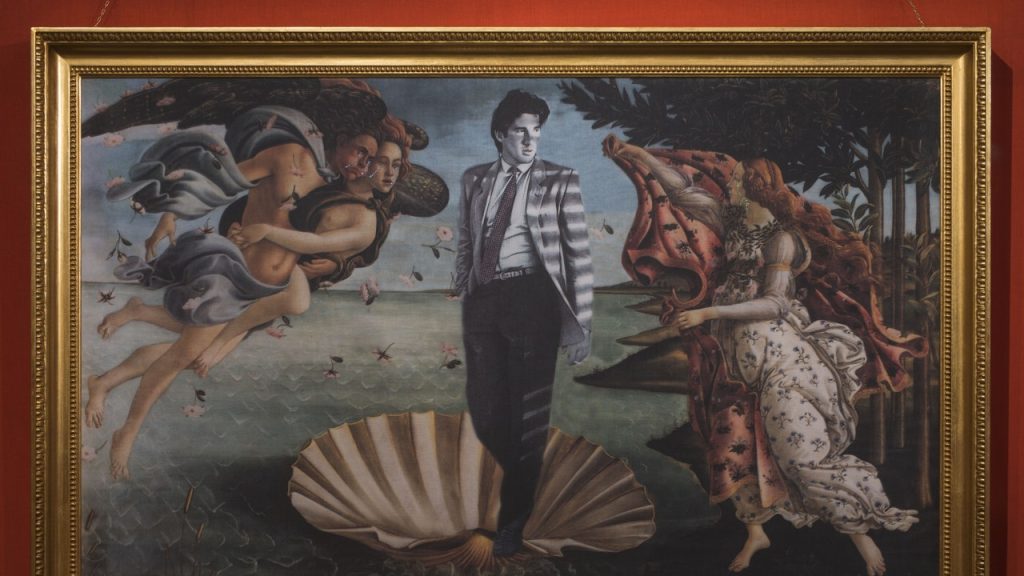

The author reflects on the challenge of confronting masterpieces by renowned artists like Michelangelo, whose imagery has become popularized in Pop culture. They acknowledge that smaller, priceless works by artists like Carpaccio, Giotto, and Bellini present an even greater challenge due to their significant contributions to the art of painting. Despite their 30-year career, the author never imagined being given the opportunity to exhibit their work in such a prestigious setting, leading them to question their ability to create art that could hold its own against these established masterpieces.

The author discusses the process of adapting their artworks to the unique and restrictive setting of Museo Correr, where nothing can be touched, changed, or moved from Scarpa’s design. They highlight the importance of respecting the space and its history, emphasizing the need to create a display that can complement and coexist with the iconic works already housed in the museum. The author recognizes the weight of showcasing their work alongside masterpieces that have shaped the art world and strives to create a dialogue between their contemporary pieces and the classical treasures on view.

The author contemplates the significance of tears as a subject in their work, noting that it has been a recurring theme since their early career. They reject the notion of strategically incorporating tears into their art for commercial gain, instead viewing them as a natural and emotional element that has not been explored in traditional art representations. The author reflects on the absence of tears in male-dominated art culture, suggesting that the portrayal of tears has historically been associated with women’s expressions of emotion through crafts like embroidery rather than through painting.

In conclusion, the author’s exhibition at Museo Correr represents a pivotal moment in their career, allowing them to confront the challenges of displaying their work alongside masterpieces by revered artists. Their exploration of tears as a central theme in their art reflects a departure from traditional representations and a desire to delve into emotional and intimate subjects. By considering the historical context of tears in art and the absence of male representation in this area, the author brings a fresh perspective to the conversation around emotion and expression in the art world.