Twelve news organizations have urged presidential nominees Joe Biden and Donald Trump to agree to debates, citing them as a “rich tradition” that has been part of every general election campaign since 1976. While Trump has indicated a willingness to debate his 2020 rival, Biden has not committed to debating him again. The news organizations, including ABC, CBS, CNN, Fox, PBS, NBC, NPR, and The Associated Press, believe that the stakes of this election are high, and there is no substitute for the candidates debating before the American people their visions for the future of the nation.

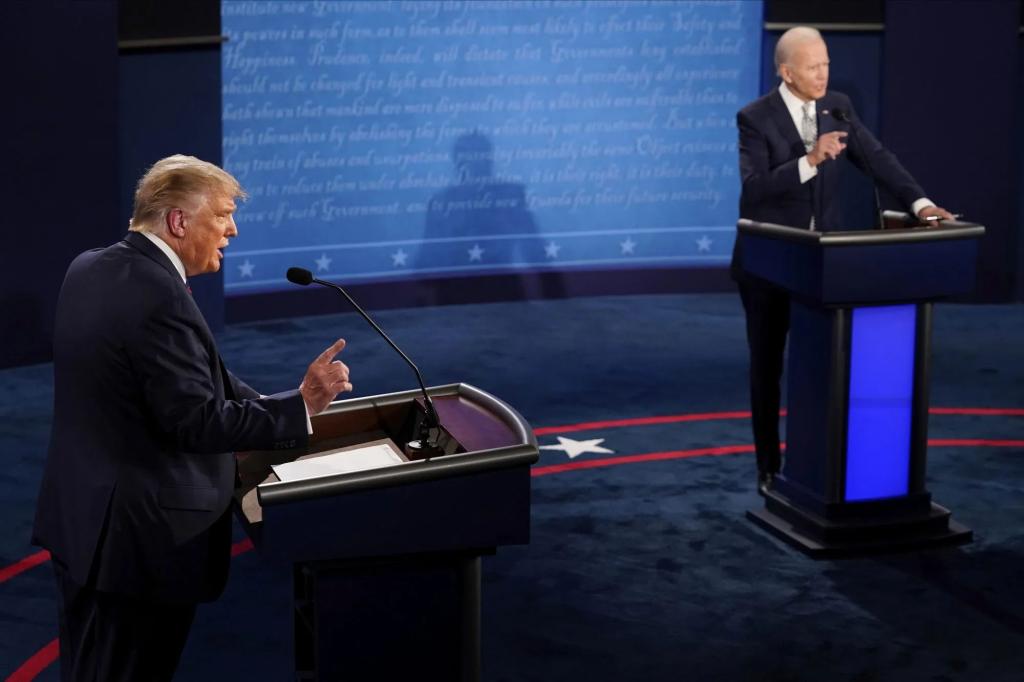

Biden and Trump debated twice in 2020, with a third debate being canceled after Trump tested positive for COVID-19. When asked if he would commit to a debate with Trump, Biden said, “it depends on his behavior.” The Trump campaign managers have expressed that the president is willing to debate anytime, any place, and anywhere and that the time to start these debates is now. They referenced the seven 1858 Illinois Senate debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas, indicating that modern America deserves as much.

The Republican National Committee decided in 2022 to no longer participate in forums sponsored by the Commission on Presidential Debates. The Trump campaign has not declared whether it will adhere to this decision but has some conditions. They want assurance that the debates are fair and impartial and have suggested that the timetable be moved up due to the number of Americans who will have already voted by the original debate dates set by the commission. The Biden campaign has not commented on the news organizations’ request but referred to the president’s earlier statement. The Trump campaign has not responded.

At a rally in northeast Pennsylvania, Trump set up two lecterns on the stage, one for him and the other symbolizing Biden’s refusal to debate. This action was meant to show that Trump is calling on Biden to debate anytime, anywhere, and any place. He emphasized that the country is heading in the wrong direction and that it is necessary to debate to explain to the American people what is going on. C-SPAN, NewsNation, and Univision have also joined the call for debates, with USA Today adding its voice. However, The Washington Post declined to be a part of the letter, and their participation could potentially bring more viewership to the debates since television news ratings are currently down compared to the 2020 campaign.

The broadcasters are seeking the energy that debates may bring as television news ratings have significantly decreased compared to the last election cycle. It is noted that there were no Democratic debates this presidential cycle, and Trump’s lack of participation in the GOP forums contributed to a lack of interest in them. The news organizations believe that the debates are crucial in giving the candidates an opportunity to share their visions for the future of the nation with the American people. Both campaigns have expressed differing views on the conditions required for agreeing to the debates, including the timing, moderators, and format of the debates. The future of the debates remains uncertain as the candidates have not publicly committed to participating in them.