Jimmy Dean, known for his iconic sausage brand, was more than just a businessman. He was a talented musician, storyteller, and TV host who helped reshape country music and breakfast culture. Born in 1928, Dean dropped out of high school at age 16 to join the U.S. Merchant Marine during World War II, before later serving in the U.S. Army Air Force. After his discharge in 1948, he formed his band, the Texas Wildcats, and gained popularity playing in various venues in Washington, D.C. It was there that he found acclaim as the host of “The Jimmy Dean Show,” a nationally televised variety program that featured top performers of the day, including Jim Henson’s Muppets.

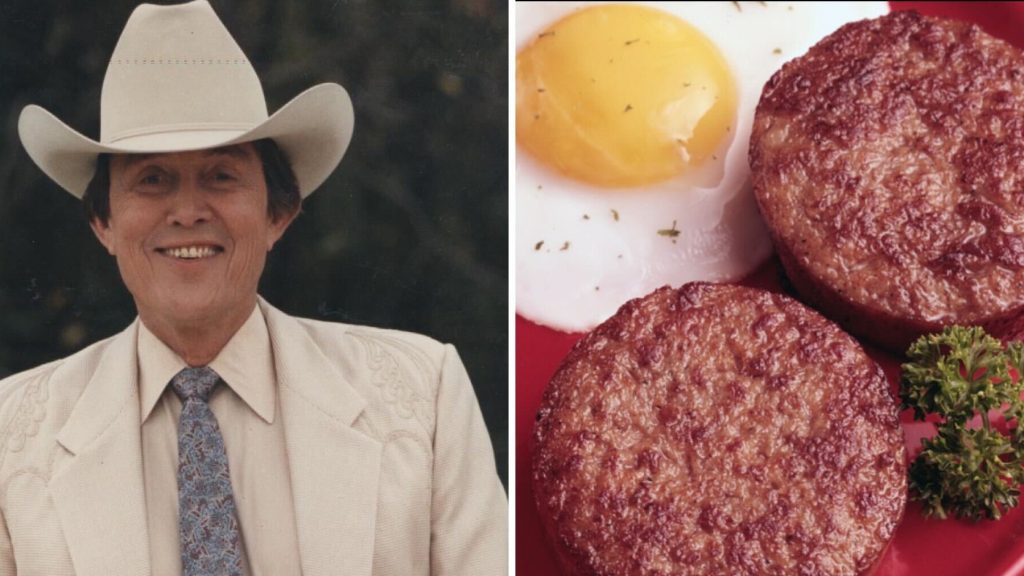

Dean’s 1961 hit song “Big, Bad John” propelled him to stardom and earned him a Grammy Award. This success allowed him to launch the Jimmy Dean Meat Co. with his brother Don in 1969. The company quickly grew in size, employing over 150 people and having an annual payroll of more than $3 million. This success also had a significant impact on his hometown of Plainview, Texas, leading to a hog boom in an area that was previously focused on cotton and cattle farming. Dean’s philanthropy extended beyond his business ventures, as he donated $1 million to Wayland Baptist University before his passing in 2010. His estate continues to support the town to this day.

Dean’s impact on popular culture and the food industry is still felt today, with his signature hit “Big Bad John” remaining a fan favorite. The song tells the story of an imposing drifter who saves 20 men in a mine collapse, with the iconic line “Here lies one hell of a man” inscribed on Dean’s gravestone in Varina, Virginia. Beyond his music and business endeavors, Dean’s legacy lives on through the Jimmy Dean Museum in Plainview, Texas, where visitors can learn about his life and contributions to the community. The museum serves as a tribute to the man who went from humble beginnings to becoming a beloved figure in American culture.

Dean’s story is one of resilience and success, as he overcame a challenging upbringing to achieve fame and fortune in the music and food industries. His dedication to his craft, as well as his commitment to giving back to his community, has left a lasting impact on those who knew him and continue to celebrate his legacy. From his early days playing in dive bars in Washington, D.C., to his rise to fame as a television host and sausage entrepreneur, Dean’s journey is a testament to the power of hard work and determination. As Americans continue to enjoy his products and music, they are also reminded of the man behind the brand and the enduring legacy he left behind.