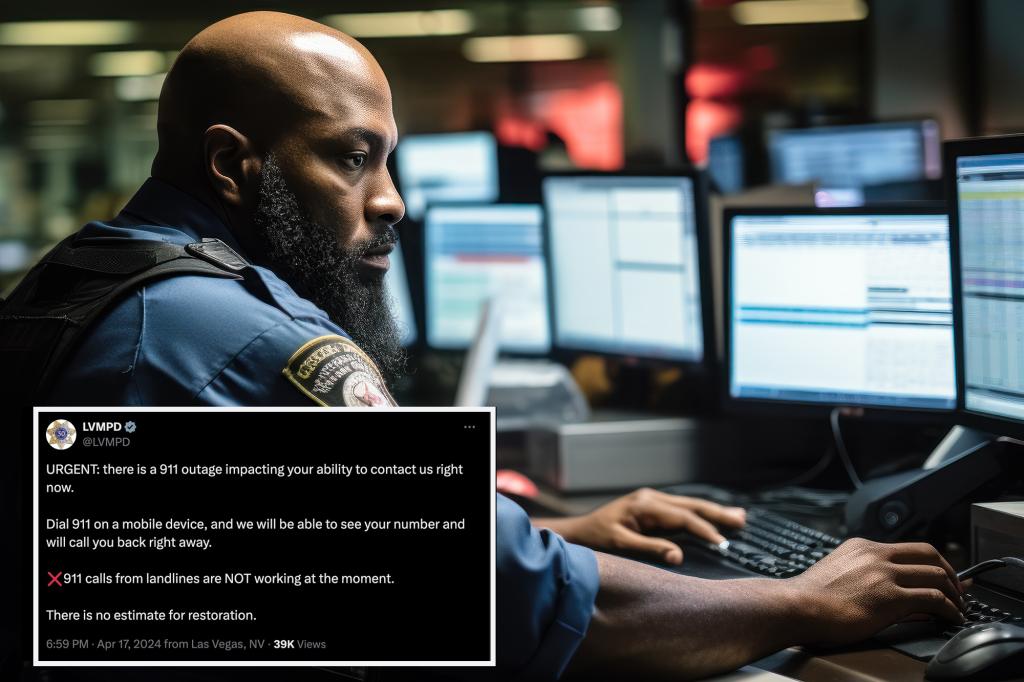

The evening of Wednesday, 911 service experienced a crash in at least three states, causing emergency outages in several municipalities in Nevada and Nebraska, as well as the entire state of South Dakota. Las Vegas police were the first to report that 911 calls were not getting through to dispatchers. The service seemingly dropped at the same time, causing a widespread interruption in emergency communication. Las Vegas Metro Police Department instructed residents to dial 911 on a mobile device so they could see the number and call back right away, as calls from landlines were not working at that moment. The roughly 656,000 residents of Las Vegas were advised to text 911 instead, as that portion of the service was not affected by the outage.

Throughout the affected areas, including Henderson, Buffalo County, and City of Kearney, residents were facing the same issue of not being able to access emergency services through the 911 system. The outages were not isolated incidents, and there was no clear timeframe provided for when the service would be restored. In Nebraska, the affected emergency call centers asked people to dial alternate, non-emergency numbers for assistance. South Dakota confirmed that the outages affected the entire state, leaving nearly 910,000 people without the ability to call 911. Rapid City Police Department warned residents against testing the system to see if their calls would go through, as unnecessary calls were affecting the workload of dispatchers and hindering their ability to respond to actual emergencies promptly. Residents were urged to avoid calling 911 unless there was a legitimate emergency.

The reason for the widespread outages and why these specific states were affected was not clear at the time. South Dakota’s connection to Nebraska through its southern border may have played a role in the simultaneous service interruptions in these states. Nevada, being approximately 1,000 miles away from either South Dakota or Nebraska, posed a geographical anomaly in terms of the affected areas. The cause of the 911 service crash was still under investigation, and emergency responders were working to address the issue and restore service as soon as possible. In the meantime, residents were being advised on alternative methods of seeking help, such as texting 911 or using non-emergency numbers to reach the appropriate authorities.

As the situation unfolded on Wednesday evening, emergency response teams in the affected states were coordinating their efforts to address the widespread 911 service outages. Dispatchers were dealing with a surge of unnecessary calls as residents tested the system, which was complicating their ability to manage actual emergencies effectively. Law enforcement agencies were urging the public to refrain from calling 911 unless there was a real emergency to allow dispatchers to focus on providing assistance to those in need. The interruption in 911 service highlighted the critical role that emergency communication systems play in ensuring public safety and the need for continued vigilance in maintaining and enhancing these vital services to protect communities in times of crisis.