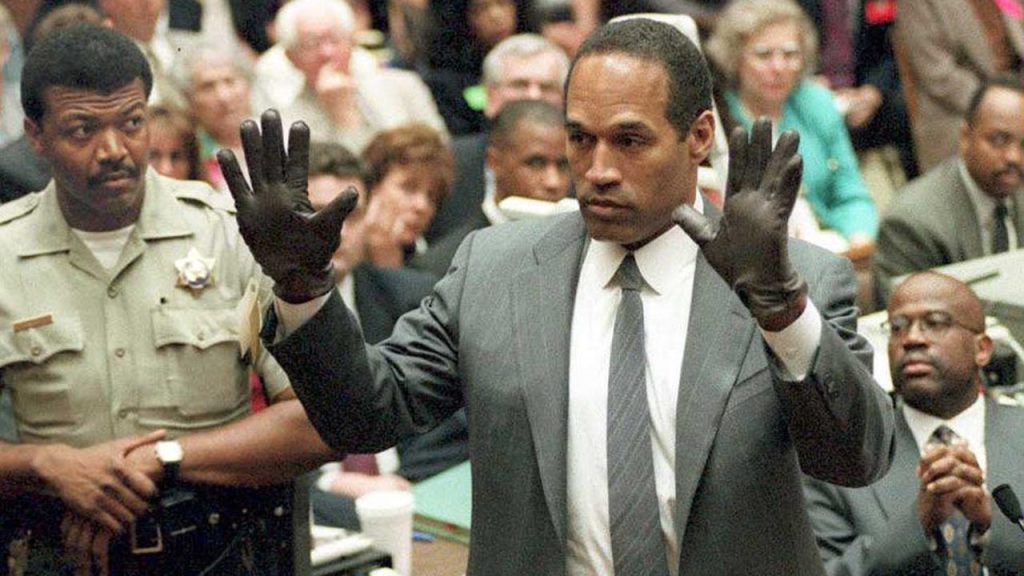

The Fox News True Crime special edition newsletter delves into the infamous 1995 trial of O.J. Simpson, which marked the beginning of America’s obsession with courtroom drama. The newsletter revisits the events that unfolded during the trial, including the introduction of TV legal eagles that became household names. It also explores the case that ultimately led to Simpson’s conviction, showcasing the dedicated Fox True Crime team that covered the story extensively.

One of the most iconic moments of the case was the Bronco chase, which rivaled the NBA Finals for attention in the sports world. The newsletter examines the impact of the murders that captured headlines, dividing the public’s attention between the high-profile trial and the competitive sports event. Additionally, the newsletter tracks the whereabouts of the infamous Bronco vehicle, which has become a symbol of a dark moment in American history and a focal point for crime aficionados.

A key figure in the O.J. Simpson case, Kato Kaelin, is also featured in the newsletter, discussing his life then and now with Jesse Watters. Kaelin gained notoriety as Simpson’s houseguest during the trial and has since navigated the complexities of fame and public scrutiny. The newsletter also highlights the Kardashian connection to the case, revealing that the family’s name was already known before their reality television stardom.

Caitlyn Jenner, formerly known as Bruce Jenner, offers candid remarks in the newsletter, bluntly stating “Good riddance” in reference to O.J. Simpson. Meanwhile, Ron Goldman’s father vows to continue seeking justice for his son, implying that Simpson’s death will not mark the end of the pursuit for closure. The newsletter presents a comprehensive look at the O.J. Simpson case, from his rise to fame as a football star to his fall from grace during the trial.

Through a collection of photographs, the newsletter traces O.J. Simpson’s journey from his beginnings in Buffalo to his affluent lifestyle in Brentwood. The visuals capture the essence of a man who once had it all but ultimately faced a grim fate due to his involvement in the double murder case. The Fox News True Crime Newsletter offers complete coverage of the O.J. Simpson case, providing readers with a detailed look at one of the most infamous trials in American history.