Tay Lautner reacted to a TikTok video imagining how Taylor Swift’s ex-boyfriends would respond to news of her new album, The Tortured Poets Department. The video featured audio of Swift announcing her album at the Grammy Awards, and Collins pretending to react as Swift’s famous exes, including Harry Styles, John Mayer, Tom Hiddleston, Jake Gyllenhaal, Joe Alwyn, and Lautner. The satirical video caught Tay’s attention, and he commented that it was accurate.

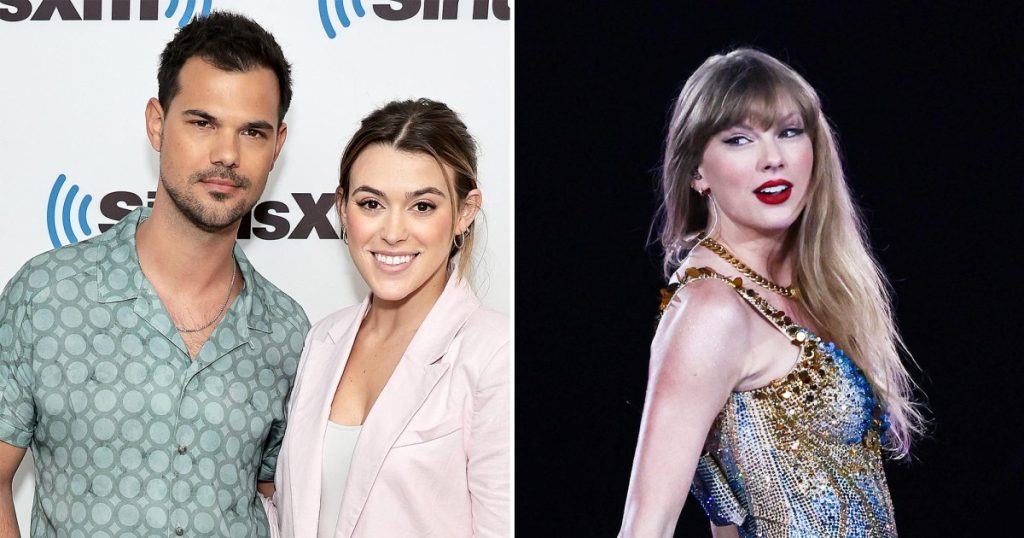

Swift and Lautner dated for four months in 2009, and it is believed that Swift’s song “Back to December” from her Speak Now album is about their relationship. Lautner has since moved on to marry Tay Dome in 2022. Despite their split, Swift and Lautner are now amicable, with Lautner even appearing in Swift’s music video for “I Can See You.” Swift premiered the music video during her Eras Tour and talked about Lautner’s impact on her life during that time.

During the music video premiere, Swift spoke about Lautner’s involvement in the video and their friendship. She mentioned that Lautner was a positive force in her life during the making of the Speak Now album. Lautner responded by praising Swift for her talent and character, expressing his respect and admiration for her. Lautner and his wife are close friends with Swift, sharing a bond through their relationship and mutual admiration.

Lautner’s wife, Tay Dome, is a huge fan of Taylor Swift and was excited to introduce her to her favorite singer. Despite any potential concerns about Lautner appearing in Swift’s music video, Dome fully supports their friendship. Lautner expressed confidence in his relationship with Dome and emphasized her supportive and understanding nature. The couple appeared on their podcast, ‘The Squeeze,’ to discuss the experience of working with Swift and their relationship dynamics.

Overall, Lautner’s reaction to the TikTok video and his involvement in Swift’s music video showcase the positive and respectful relationship he has with his ex-girlfriend, Taylor Swift. The friendship between Lautner, Swift, and Dome is strong, with mutual admiration and support evident in their interactions. Despite the complexities of past relationships, they have managed to maintain a healthy and cordial dynamic, highlighting the maturity and understanding of all parties involved.