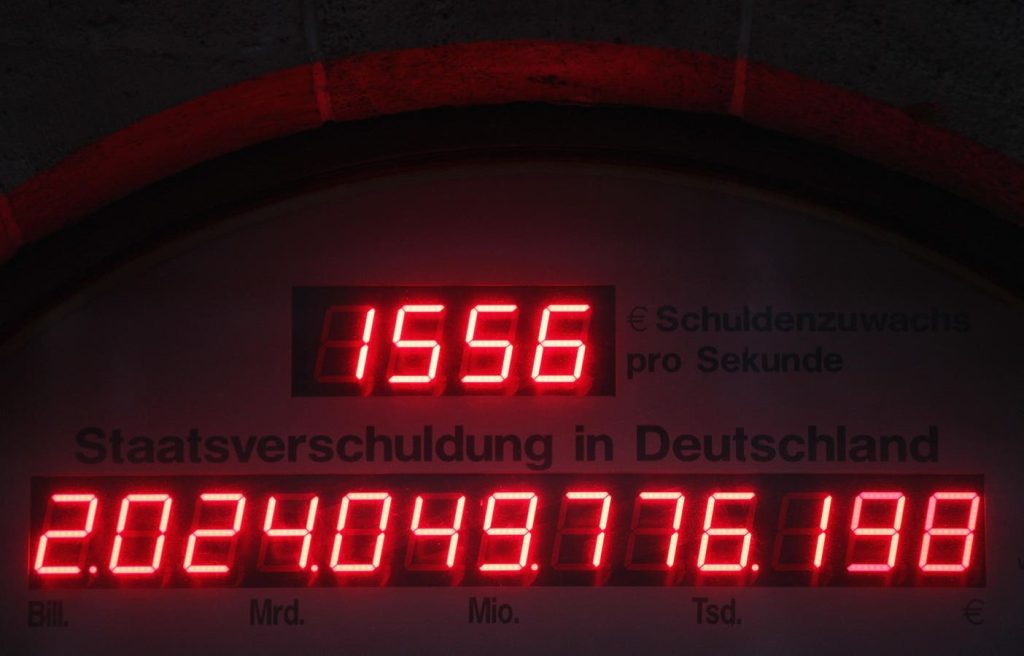

The beginning of the week saw several warnings about rising debt levels, sparking alarm among policymakers and financial experts. The French government reported a higher-than-expected deficit, contributing to a growing burden of debt. Larry Fink, the head of a major financial institution, warned of the escalating levels of debt accumulation globally. Additionally, the Congressional Budget Office in the US highlighted the rising debt levels, projecting a concerning trajectory of debt to GDP for the US government.

The issue of rising debt has become a major concern, with implications for economic growth and global stability. High debt levels are seen as a barrier to sustained economic growth, with many large nations facing substantial levels of debt that need to be addressed. The impact of high indebtedness is not only economic but also political, shaping power dynamics and international relations among nations.

Despite the lessons learned from the global financial crisis, the policy community seems to have forgotten the need to address the root causes of the crisis, including excessive debt. The recommendations and insights from key books written in the aftermath of the crisis have largely been ignored, leading to a normalization of high levels of public debt. The UK, for example, has seen a dramatic increase in public debt since the financial crisis, indicating a lack of progress in addressing the underlying issues.

The rise of indebtedness is also linked to other crises, such as climate change, with global temperatures and debt levels rising in tandem. However, policymakers have been slow to respond to these interconnected issues, assuming that central banks can manage the risks associated with high debt levels. The adaptation of the economic system to accommodate increasing debt has created a false sense of security, leading to potential risks that go unnoticed.

The concept of an ‘Age of Debt’ reflects the current economic environment, where high debt levels are perceived as normal and manageable. This trend is fueled by the growth of the ‘debt industry’, including private credit firms and fintech companies that provide lending services. These firms operate outside traditional banking regulations, increasing the overall risk within the financial system. As the debt industry expands, the risks associated with rising debt become more focused on individual countries, potentially destabilizing national financial systems.

In the 21st century, the ability of nations to manage and reduce their debt levels will be a key determinant of their economic success and stability. The interconnected nature of the global financial system means that national debt levels can have far-reaching implications, impacting both domestic economies and international markets. As the ‘Age of Debt’ continues to evolve, it will be crucial for policymakers to address the root causes of rising debt and work towards sustainable solutions to ensure long-term economic prosperity.