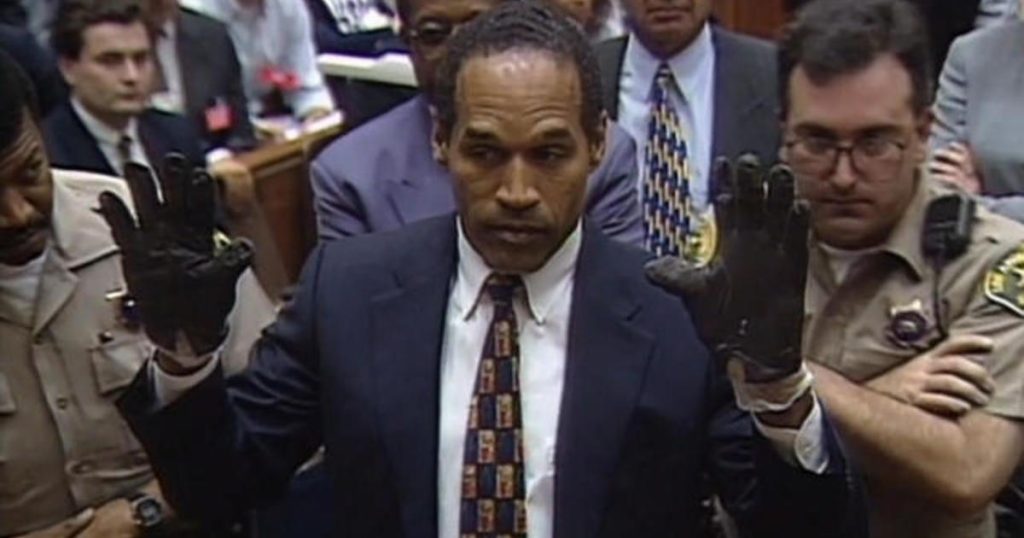

The CBS Evening News highlighted two stories in its broadcast: a look back at the complicated life of O.J. Simpson and the announcement that legendary announcer Verne Lundquist will be calling his final Masters Tournament. The segment on O.J. Simpson delved into the rise and fall of the former football star, who was acquitted of the murders of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend, Ron Goldman, in a highly publicized trial in 1995. Simpson’s life has been marked by controversy, including his arrest and subsequent conviction for armed robbery and kidnapping in 2007. Despite his legal troubles, Simpson remains a polarizing figure in American culture.

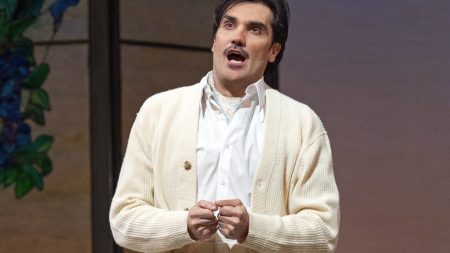

Verne Lundquist, on the other hand, is a beloved and respected sports announcer who has been a fixture in the industry for decades. He is best known for his work on college football and basketball games, as well as golf tournaments like the Masters. Lundquist has announced that the upcoming Masters Tournament will be his last, marking the end of an era in sports broadcasting. His retirement is being met with both sadness and appreciation from fans and colleagues who have admired his talent and professionalism over the years.

The segment on O.J. Simpson touched on the impact that his trial and legal troubles have had on his legacy. Despite being acquitted of murder, Simpson’s reputation has been tarnished by the allegations of domestic violence and criminal behavior that have plagued him throughout his life. The trial itself was a media circus that captivated the nation, with many people divided on Simpson’s guilt or innocence. The segment highlighted the enduring fascination with Simpson and the ongoing debate about his culpability in the deaths of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman.

In contrast, the announcement of Verne Lundquist’s retirement focused on the admiration and respect that he has garnered over the course of his career. Lundquist’s voice has become synonymous with some of the most iconic moments in sports history, and his departure from the broadcasting world will undoubtedly leave a void for fans who have come to appreciate his expertise and passion for the game. The segment included interviews with colleagues and sports analysts who praised Lundquist for his talent and dedication to his craft, making it clear that his presence will be sorely missed in the industry.

Ultimately, the stories of O.J. Simpson and Verne Lundquist serve as reminders of the complexities and contradictions that exist within the world of sports and entertainment. While Simpson’s legacy is tainted by scandal and tragedy, Lundquist’s career is celebrated for its longevity and impact on the industry. Both men have left indelible marks on their respective fields, albeit in vastly different ways. As Simpson continues to navigate the aftermath of his legal troubles, Lundquist will be stepping away from the spotlight with a legacy that is sure to endure for years to come.

In conclusion, the CBS Evening News segment provided viewers with a thoughtful reflection on two figures who have had a profound influence on American culture. O.J. Simpson’s tumultuous life and legal battles have sparked endless debate and speculation, while Verne Lundquist’s distinguished career has earned him the respect and admiration of fans and colleagues alike. As these two men occupy different spheres of influence, their stories serve as a reminder of the complexities and contradictions that are inherent in the world of sports and entertainment. Despite the divergent paths they have taken, both Simpson and Lundquist have left lasting legacies that will continue to shape the narratives of their respective fields for years to come.